Rejected Book Proposal: Metal Machine Music

So this is my first rejected-book-proposal post . . . I'm hoping it will be my last . . . and if it's not, at least I can say I'm assembling a Ghost Library of my unwritten books.

This book proposal was for Continuum Publishing's 33 and 1/3 series, "of short books about critically acclaimed and much-loved albums of the last 40 years." I proposed a book about Metal Machine Music, Lou Reed's double-LP recording of 1975.

One has many regrets as soon as one has irrevocably submitted a book proposal. One could have misspelled an important name or overlooked an embarrassing grammatical error, for instance, or mixed up one's facts or dates or mentioned that I've never listened to the record I'm proposing to write about (at least not all the way through). One may also wonder if one shouldn't have implied that he is insane in the first sentence of his proposal -- or if music-book publishers ever avoid writers who refer to their subjects as "novelty records" or "a bad joke," "the figurative dead-end of pop music listening." (Maybe it was unwise to admit that I didn't think Metal Machine Music was "a fully realized avant-garde composition" or even "a work of art.")

Perhaps it was a bad idea from the start, to propose to write a book for people who are unusually attached to their records at a moment when I'm desperate to detach myself from mine . . .

[Note: the proposal was to include my name; a brief outline (up to 1000 words); a brief bio of myself explaining why I'm the best person to write about that album (up to 500 words); and a couple of sentences on which 33 1/3 book I've enjoyed the most so far, and why.]

Outline: Metal Machine Music

Perhaps I'm mad. Lou Reed's Metal Machine Music has been ranked among the worst records ever released by a respected rock musician and I'm proposing to write a book about it. Surely I'm deranged -- a four-sided LP, more than an hour long, consisting of nothing but amplifier feedback; a rip-off, as many of its original customers claimed when they returned it to the store and demanded their money back. Alright, then, suppose I am deranged . . . but only enough for the task with which I ask you to appoint me. After all, Reed was at the peak of his popularity when he released Metal Machine Music, which he considered an electronic masterpiece with "about seven thousand different melodies," "harmonic buildup," and "infinite ways of listening." Instinct suggests it was either an ingenious prank or a misguided attempt to recover Reed's waning 'street' credibility, but I'm more than happy to take Reed and the record's advocates seriously, suspend my disbelief, and consider Metal Machine Music a fully realized avant-garde composition; evaluate the record in terms of Stockhausen and Xenakis; survey its impact on the so-called noise, industrial, and ambient genres of rock 'n' roll -- Merzbow, Throbbing Gristle, My Bloody Valentine.

Surely I'm deranged -- a four-sided LP, more than an hour long, consisting of nothing but amplifier feedback; a rip-off, as many of its original customers claimed when they returned it to the store and demanded their money back. Alright, then, suppose I am deranged . . . but only enough for the task with which I ask you to appoint me. After all, Reed was at the peak of his popularity when he released Metal Machine Music, which he considered an electronic masterpiece with "about seven thousand different melodies," "harmonic buildup," and "infinite ways of listening." Instinct suggests it was either an ingenious prank or a misguided attempt to recover Reed's waning 'street' credibility, but I'm more than happy to take Reed and the record's advocates seriously, suspend my disbelief, and consider Metal Machine Music a fully realized avant-garde composition; evaluate the record in terms of Stockhausen and Xenakis; survey its impact on the so-called noise, industrial, and ambient genres of rock 'n' roll -- Merzbow, Throbbing Gristle, My Bloody Valentine.

In doing so, however, I should be careful not to be carried away by the idea of Metal Machine Music as a serious work (like the German fellow who recently transcribed and arranged it for a 40-piece orchestra). When Lester Bangs, the well-known author of "A Reasonable Guide to Horrible Noise," named it "The Greatest Album Ever Made," he wasn't entirely sincere. Although Bangs said he liked the record -- and I believe that in some sense he did -- supposedly he listened to it constantly and eagerly played it for all his friends (much to their dismay), in print he called it a "migraine" and suggested, "that as classical music it added nothing to a genre that may well be depleted." He added: "As a statement it's great, as a giant FUCK YOU it shows integrity -- a sick, twisted, dunced-out, malevolent, perverted, psychopathic integrity. . . ." Yet I sense that, for Bangs, who is somewhat responsible for the record's enduring cult status, Metal Machine Music was more of a bizarre novelty than a work of art. This is not necessarily an insult. Bangs loved novelty records and consistently mentioned them in his articles and reviews. For him, and I think for any music geek, the novelty record adds personality to a record collection that might otherwise seem caste from a mold. Let me offer an example. A while ago I downloaded the first half of Metal Machine Music onto my iPod. I listened to it closely several times and, after a while, found I most enjoyed playing the record in the background at parties without telling anyone, then waiting to see how long it would take before my guests began to notice and complain. (Longer than you might think. Usually at least fifteen minutes, which is surprising when I explain that, by party, I mean a quiet gathering of perhaps twelve friends -- none of whom are particularly interested in electronic music or distortion.)

This anecdote serves several purposes. One is to show off my terrific sense of humor. Another is to prove that, like Bangs, I have an imaginative feel for what a record is, or should be. The truly dedicated listener, after all, aspires to something greater than good taste. Since the records he collects, studies, and really enjoys are also, as I have told myself, the very elements of being, it becomes necessary to convince, not only himself, but indeed everyone he knows, that they are not merely the commercial products of a vast and indifferent industry. By proclaiming affection for a record that almost no one would honestly say that he or she likes, whether it's Metal Machine Music or a musical adaptation of Finnegans Wake, the listener seems to achieve a rare moment of individuality and surprise among a lifetime of prefabricated certainty. Of course, it's possible that what he really achieves is only solitude and isolation. Bangs once suggested that Metal Machine Music was a "kind of ultimate antisocial act." Thirty-seven years later, the record still has a reputation for being aggressive, hostile, and off-putting. Is alienation, finally, the price of individuality in a mechanical age? If one really believes in Metal Machine Music, it is -- most likely -- as an indictment of the pop album's capacity for self-expression. The record has no songs and, in spite of what Reed may claim, no melodies or harmonies, and only the vaguest, crudest sense of rhythm. Though it came in the same gatefold, double-vinyl package as Exile on Main St. and The Beatles (white album), it refused to be identified with on the terms to which the listeners of those records were accustomed. Those who could identify with the record on its terms, a barrage of distortion and screaming feedback that was literally endless -- the fourth side of the LP* ended in a locked groove, which played the final seconds over and over until the listener decided to turn it off -- became the figurative dead-end of pop music listening, obliged to manually terminate their relationship with a potentially dangerous noise that had no foreseeable purpose or conclusion.

For the moment, however, as I look forward to transforming Metal Machine Music into a book, I prefer to see its infinite drone, not as a dead end, but as a starting point for fresh discussion; a blank slate to write upon without having to worry about fitting my statements into a context that is already set and fixed. The listening body has invested much less in Metal Machine Music than Blonde on Blonde, and this lack of preconception should allow for a greater freedom to examine both the potential and limitations of the pop album honestly. Metal Machine Music may have the reputation of a bad joke, but I'm excited by the possibility of taking that joke seriously and hopeful that, within its void, there may be a chance for renewal.

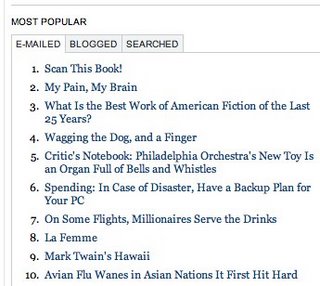

*The eight-track tape version of Metal Machine Music (pictured above) automatically looped from one side to the next, over and over, with no breaks whatsoever. [Incidentally, the photo of the eight-tracks and this caption were not included in the original proposal.]

Bio: John Uhl

Hopefully my outline has already given you some sense of my personality and relative talents as a writer. Generally, when I write, I try to allow my biography to emerge gradually, through inference and connotation. At this point what's important to know about me is that I care about records and music, in particular their potential to express truth, such that I refuse to sentimentalize my relationship with them. I may be a fan of Lou Reed's work with the Velvet Underground, but I consider his solo career erratic and have no strong convictions about Metal Machine Music, one way or the other. I haven't even listened to it all the way through (I could only find half of it online), and see no reason why this should make me less qualified to write one of your books than someone who listens to it (or some other widely beloved record) everyday, start to finish. Popular music places too much emphasis on the fan's perspective and, frankly, I think it would be more interesting to read a book in which the author worked toward a new conclusion -- rather than against his, her, or the public's bias. Of course, I have my own biases, which present themselves clearly whenever they are needed, but -- in this case -- these don't pertain to my esteem for the record that would be up for discussion.

[At this point I included two paragraphs of professional biographical information that I will refrain from publishing here.]

Thoughts on the 33 1/3 series

So far, my favorite books in the series have been:

OK Computer, because I enjoyed its numerous musical charts.

Led Zeppelin IV, because even though it addressed a record and subject (the occult) about which I had no interest in reading, I got through at least half the book.

Celine Dion's Let's Talk About Love, which I like in theory, because it seems a ridiculous choice of subject and suggests a willingness on the publisher's part to take on ostensibly imprudent projects.

-- proposal written, 02.14.07

Other Rejected 33 1/3 Proposals

Jerry Lee Lewis, "Live At The Star Club, Hamburg," by Keith Phipps

Jefferson Airplane, "Crown of Creation," by Tim Lucas (this one doesn't include the actual proposal, but is interesting)

The Jesus and Mary Chain, "Psychocandy," by Daniel Fuller

Butthole Surfers, "Locust Abortion Technitian," by Antonio Lopez

Bonny 'Prince' Billy, "I See a Darkness," by Mike Hotter

Cheap Trick, "Dream Police," by Matt Cibula

Peter Gabriel, "So," by Nik Dirga

Sufjan Stevens, "Illinois," by Benjamin Squires

Soft Cell, "Non-Stop Erotic Cabaret," by Kurt B. Reighley

The Dukes of Stratosphear (XTC), "Chips from the Chocolate Fireball," by Paul Margach

Buffalo Springfield, "Buffalo Springfield Again," by Bryan Thomas

Bright Eyes, "Fevers and Mirrors," by Sarah Feldman

Isaac Hayes, "Shaft," by AKA

Phish, "Hoist," by Dave Heaton

This book proposal was for Continuum Publishing's 33 and 1/3 series, "of short books about critically acclaimed and much-loved albums of the last 40 years." I proposed a book about Metal Machine Music, Lou Reed's double-LP recording of 1975.

One has many regrets as soon as one has irrevocably submitted a book proposal. One could have misspelled an important name or overlooked an embarrassing grammatical error, for instance, or mixed up one's facts or dates or mentioned that I've never listened to the record I'm proposing to write about (at least not all the way through). One may also wonder if one shouldn't have implied that he is insane in the first sentence of his proposal -- or if music-book publishers ever avoid writers who refer to their subjects as "novelty records" or "a bad joke," "the figurative dead-end of pop music listening." (Maybe it was unwise to admit that I didn't think Metal Machine Music was "a fully realized avant-garde composition" or even "a work of art.")

Perhaps it was a bad idea from the start, to propose to write a book for people who are unusually attached to their records at a moment when I'm desperate to detach myself from mine . . .

***

[Note: the proposal was to include my name; a brief outline (up to 1000 words); a brief bio of myself explaining why I'm the best person to write about that album (up to 500 words); and a couple of sentences on which 33 1/3 book I've enjoyed the most so far, and why.]

Outline: Metal Machine Music

Perhaps I'm mad. Lou Reed's Metal Machine Music has been ranked among the worst records ever released by a respected rock musician and I'm proposing to write a book about it.

Surely I'm deranged -- a four-sided LP, more than an hour long, consisting of nothing but amplifier feedback; a rip-off, as many of its original customers claimed when they returned it to the store and demanded their money back. Alright, then, suppose I am deranged . . . but only enough for the task with which I ask you to appoint me. After all, Reed was at the peak of his popularity when he released Metal Machine Music, which he considered an electronic masterpiece with "about seven thousand different melodies," "harmonic buildup," and "infinite ways of listening." Instinct suggests it was either an ingenious prank or a misguided attempt to recover Reed's waning 'street' credibility, but I'm more than happy to take Reed and the record's advocates seriously, suspend my disbelief, and consider Metal Machine Music a fully realized avant-garde composition; evaluate the record in terms of Stockhausen and Xenakis; survey its impact on the so-called noise, industrial, and ambient genres of rock 'n' roll -- Merzbow, Throbbing Gristle, My Bloody Valentine.

Surely I'm deranged -- a four-sided LP, more than an hour long, consisting of nothing but amplifier feedback; a rip-off, as many of its original customers claimed when they returned it to the store and demanded their money back. Alright, then, suppose I am deranged . . . but only enough for the task with which I ask you to appoint me. After all, Reed was at the peak of his popularity when he released Metal Machine Music, which he considered an electronic masterpiece with "about seven thousand different melodies," "harmonic buildup," and "infinite ways of listening." Instinct suggests it was either an ingenious prank or a misguided attempt to recover Reed's waning 'street' credibility, but I'm more than happy to take Reed and the record's advocates seriously, suspend my disbelief, and consider Metal Machine Music a fully realized avant-garde composition; evaluate the record in terms of Stockhausen and Xenakis; survey its impact on the so-called noise, industrial, and ambient genres of rock 'n' roll -- Merzbow, Throbbing Gristle, My Bloody Valentine.In doing so, however, I should be careful not to be carried away by the idea of Metal Machine Music as a serious work (like the German fellow who recently transcribed and arranged it for a 40-piece orchestra). When Lester Bangs, the well-known author of "A Reasonable Guide to Horrible Noise," named it "The Greatest Album Ever Made," he wasn't entirely sincere. Although Bangs said he liked the record -- and I believe that in some sense he did -- supposedly he listened to it constantly and eagerly played it for all his friends (much to their dismay), in print he called it a "migraine" and suggested, "that as classical music it added nothing to a genre that may well be depleted." He added: "As a statement it's great, as a giant FUCK YOU it shows integrity -- a sick, twisted, dunced-out, malevolent, perverted, psychopathic integrity. . . ." Yet I sense that, for Bangs, who is somewhat responsible for the record's enduring cult status, Metal Machine Music was more of a bizarre novelty than a work of art. This is not necessarily an insult. Bangs loved novelty records and consistently mentioned them in his articles and reviews. For him, and I think for any music geek, the novelty record adds personality to a record collection that might otherwise seem caste from a mold. Let me offer an example. A while ago I downloaded the first half of Metal Machine Music onto my iPod. I listened to it closely several times and, after a while, found I most enjoyed playing the record in the background at parties without telling anyone, then waiting to see how long it would take before my guests began to notice and complain. (Longer than you might think. Usually at least fifteen minutes, which is surprising when I explain that, by party, I mean a quiet gathering of perhaps twelve friends -- none of whom are particularly interested in electronic music or distortion.)

This anecdote serves several purposes. One is to show off my terrific sense of humor. Another is to prove that, like Bangs, I have an imaginative feel for what a record is, or should be. The truly dedicated listener, after all, aspires to something greater than good taste. Since the records he collects, studies, and really enjoys are also, as I have told myself, the very elements of being, it becomes necessary to convince, not only himself, but indeed everyone he knows, that they are not merely the commercial products of a vast and indifferent industry. By proclaiming affection for a record that almost no one would honestly say that he or she likes, whether it's Metal Machine Music or a musical adaptation of Finnegans Wake, the listener seems to achieve a rare moment of individuality and surprise among a lifetime of prefabricated certainty. Of course, it's possible that what he really achieves is only solitude and isolation. Bangs once suggested that Metal Machine Music was a "kind of ultimate antisocial act." Thirty-seven years later, the record still has a reputation for being aggressive, hostile, and off-putting. Is alienation, finally, the price of individuality in a mechanical age? If one really believes in Metal Machine Music, it is -- most likely -- as an indictment of the pop album's capacity for self-expression. The record has no songs and, in spite of what Reed may claim, no melodies or harmonies, and only the vaguest, crudest sense of rhythm. Though it came in the same gatefold, double-vinyl package as Exile on Main St. and The Beatles (white album), it refused to be identified with on the terms to which the listeners of those records were accustomed. Those who could identify with the record on its terms, a barrage of distortion and screaming feedback that was literally endless -- the fourth side of the LP* ended in a locked groove, which played the final seconds over and over until the listener decided to turn it off -- became the figurative dead-end of pop music listening, obliged to manually terminate their relationship with a potentially dangerous noise that had no foreseeable purpose or conclusion.

For the moment, however, as I look forward to transforming Metal Machine Music into a book, I prefer to see its infinite drone, not as a dead end, but as a starting point for fresh discussion; a blank slate to write upon without having to worry about fitting my statements into a context that is already set and fixed. The listening body has invested much less in Metal Machine Music than Blonde on Blonde, and this lack of preconception should allow for a greater freedom to examine both the potential and limitations of the pop album honestly. Metal Machine Music may have the reputation of a bad joke, but I'm excited by the possibility of taking that joke seriously and hopeful that, within its void, there may be a chance for renewal.

*The eight-track tape version of Metal Machine Music (pictured above) automatically looped from one side to the next, over and over, with no breaks whatsoever. [Incidentally, the photo of the eight-tracks and this caption were not included in the original proposal.]

Bio: John Uhl

Hopefully my outline has already given you some sense of my personality and relative talents as a writer. Generally, when I write, I try to allow my biography to emerge gradually, through inference and connotation. At this point what's important to know about me is that I care about records and music, in particular their potential to express truth, such that I refuse to sentimentalize my relationship with them. I may be a fan of Lou Reed's work with the Velvet Underground, but I consider his solo career erratic and have no strong convictions about Metal Machine Music, one way or the other. I haven't even listened to it all the way through (I could only find half of it online), and see no reason why this should make me less qualified to write one of your books than someone who listens to it (or some other widely beloved record) everyday, start to finish. Popular music places too much emphasis on the fan's perspective and, frankly, I think it would be more interesting to read a book in which the author worked toward a new conclusion -- rather than against his, her, or the public's bias. Of course, I have my own biases, which present themselves clearly whenever they are needed, but -- in this case -- these don't pertain to my esteem for the record that would be up for discussion.

[At this point I included two paragraphs of professional biographical information that I will refrain from publishing here.]

Thoughts on the 33 1/3 series

So far, my favorite books in the series have been:

OK Computer, because I enjoyed its numerous musical charts.

Led Zeppelin IV, because even though it addressed a record and subject (the occult) about which I had no interest in reading, I got through at least half the book.

Celine Dion's Let's Talk About Love, which I like in theory, because it seems a ridiculous choice of subject and suggests a willingness on the publisher's part to take on ostensibly imprudent projects.

-- proposal written, 02.14.07

***

Other Rejected 33 1/3 Proposals

Jerry Lee Lewis, "Live At The Star Club, Hamburg," by Keith Phipps

Jefferson Airplane, "Crown of Creation," by Tim Lucas (this one doesn't include the actual proposal, but is interesting)

The Jesus and Mary Chain, "Psychocandy," by Daniel Fuller

Butthole Surfers, "Locust Abortion Technitian," by Antonio Lopez

Bonny 'Prince' Billy, "I See a Darkness," by Mike Hotter

Cheap Trick, "Dream Police," by Matt Cibula

Peter Gabriel, "So," by Nik Dirga

Sufjan Stevens, "Illinois," by Benjamin Squires

Soft Cell, "Non-Stop Erotic Cabaret," by Kurt B. Reighley

The Dukes of Stratosphear (XTC), "Chips from the Chocolate Fireball," by Paul Margach

Buffalo Springfield, "Buffalo Springfield Again," by Bryan Thomas

Bright Eyes, "Fevers and Mirrors," by Sarah Feldman

Isaac Hayes, "Shaft," by AKA

Phish, "Hoist," by Dave Heaton

***

Update

Of 449 submitted proposals, 21 have been selected for publication. A list of the selected proposals can be seen on the 33 1/3 blog.

See an excerpt from an accepted proposal here: Israel Kamakawiwo'ole, "Facing Future," by Dan Kois

Of 449 submitted proposals, 21 have been selected for publication. A list of the selected proposals can be seen on the 33 1/3 blog.

See an excerpt from an accepted proposal here: Israel Kamakawiwo'ole, "Facing Future," by Dan Kois

Labels: 33 1/3, books, great records, Metal Machine Music, music blogs, rejected book proposals, The List