Unbinding the Universal Library: A Response to "Scan This Book!"

Now that my good friend Mr. WD has made a more formal critique of my last post, I should admit that -- in that case, at least -- my sweeping tone and will to generalize were perhaps a little excessive. I have a tendency to conflate certain idea-connections that seem obvious in my head but lack a genuine basis in the real world -- which is why I always reserve the right to revise myself. I agree with Mr. WD's suggestion that television holds the primary responsibility for our lowered attention spans and the current situation in which "publications that feature thoughtful, challenging, multi-page essays have seen a precipitous decline," as well as his conclusion: "If it is indeed the case that Americans' attention spans are significantly lower than they were 50 years ago . . . then it is incumbent upon us overeducated leftists to get better at 21st century 'message crafting.'" Nevertheless, I can't help voicing a few reservations as we plunge headlong into the sea of sound bites.

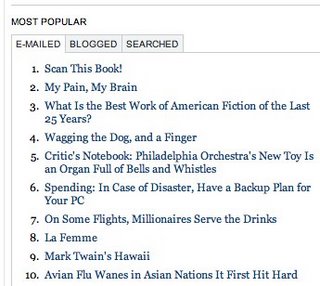

Now that my good friend Mr. WD has made a more formal critique of my last post, I should admit that -- in that case, at least -- my sweeping tone and will to generalize were perhaps a little excessive. I have a tendency to conflate certain idea-connections that seem obvious in my head but lack a genuine basis in the real world -- which is why I always reserve the right to revise myself. I agree with Mr. WD's suggestion that television holds the primary responsibility for our lowered attention spans and the current situation in which "publications that feature thoughtful, challenging, multi-page essays have seen a precipitous decline," as well as his conclusion: "If it is indeed the case that Americans' attention spans are significantly lower than they were 50 years ago . . . then it is incumbent upon us overeducated leftists to get better at 21st century 'message crafting.'" Nevertheless, I can't help voicing a few reservations as we plunge headlong into the sea of sound bites.Allow me to refer to the article I mentioned in yesterday's comments section: "Scan This Book!" by Kevin Kelly, currently the most e-mailed article on NYTimes.com. The article focuses on Google's endeavor to scan the books of five research libraries to make their contents searchable online and the idea of a so-called universal library that will contain in one place a record of all human knowledge, past and present. Every book, every article, every painting, photograph, film, piece of music, web page -- all of it "fully digitized" on 50 petabyte hard disks. "Today you need a building about the size of a small-town library to house 50 petabytes. With tomorrow's technology, it will all fit onto your iPod. When that happens, the library of all libraries will ride in your purse or wallet -- if it doesn't plug directly into your brain with thin white cords."

I'm put off by the tenor of this article; by its unrelentingly optimistic view that the creation of such a library is not only inevitable, but inevitably good. First of all, I don't necessarily believe it can be done (or at least done as well as Kelly envisions it). Kelly spends much of the second half of the article detailing the numerous copyright-oriented obstacles that stand in the way of completing the book digitization process, but never doubts the final inescapability of that digitization. He refers to the Great Library of Alexandria as the predecessor to his universal library, as if to suggest it can be -- and has already been -- done, but makes nothing of the fact that we remember the library of Alexandria primarily for the fact that it burned down. Its place in our collective imagination is as an embodiment of lost knowledge. Am I the only one left with any qualms about putting all our intellectual eggs into one digital basket, so to speak? I can't help feeling unsettled by the idea that the best way for us to store information is no longer in the form of an accumulation of bound volumes, but rather a single stream of 1s and 0s that reside on a server (or servers) owned by Google. (Kelly hasn't advocated for getting rid of our paper libraries, but he implies that regular books are inherently limited and delights in listing the seemingly unlimited benefits of his own universal library.)

In point of fact, the notion of achieving unlimited knowledge is one fraught with a series of deep, mythical reservations: think Faust or Prometheus. I am reminded of the men in Gabriel Garcia Marquez's "One Hundred Years of Solitude," who invest the better part of their lives trying to decipher a series of nearly magical, knowledge-bearing parchments -- a quest that succeeds, but ultimately dooms the lineage of these men and their civilization forever (**Spoiler Alert: these are the last two and a half sentences of the book!**):

" . . . [Aureliano] began to decipher the instant that he was living, deciphering it as he lived it, prophesying himself in the act of deciphering the last page of the parchments, as if he were looking into a speaking mirror. Then he skipped again to anticipate the predictions and ascertain the date and circumstances of his death. Before reaching the final line, however, he had already understood that he would never leave the room, for it was foreseen that the city of mirrors (or mirages) would be wiped out by the wind and exiled from the memory of men at the precise moment when Aureliano Babilonia would finish deciphering the parchments, and that everything written on them was unrepeatable since time immemorial and forever more, because races condemned to one hundred years of solitude did not have a second opportunity on earth."

The Internet is this city of mirrors (or mirages): an interconnected series of words and images -- not of objects, but of reflections of objects and reflections of reflections of objects.

The digital age, as Kelly suggests, is one in which we are so glutted with copies of objects that finally the copies no longer have any value. This is more than a threat to current business models (Kelly's idea), it suggests that we have embarked upon an entirely new form of perception -- one that no longer relies on observations of the world, but on a rearrangement and resorting of those observations of the world that have already been documented. Perhaps this is what I was getting at in my last post when I referred to a "growing mistrust of facts" . . . television and the Internet are less interested in coming to an understanding of the world than in creating a dazzling manipulation of that world by means of the screen and a series of refracted, electronically beamed lights. I can't help wondering whether, if we continue on this trajectory, the twenty-first century will finally lose touch with reality to such an extent that it winds up like Marquez's Macondo: wiped out by the wind and exiled from the memory of men.

The digital age, as Kelly suggests, is one in which we are so glutted with copies of objects that finally the copies no longer have any value. This is more than a threat to current business models (Kelly's idea), it suggests that we have embarked upon an entirely new form of perception -- one that no longer relies on observations of the world, but on a rearrangement and resorting of those observations of the world that have already been documented. Perhaps this is what I was getting at in my last post when I referred to a "growing mistrust of facts" . . . television and the Internet are less interested in coming to an understanding of the world than in creating a dazzling manipulation of that world by means of the screen and a series of refracted, electronically beamed lights. I can't help wondering whether, if we continue on this trajectory, the twenty-first century will finally lose touch with reality to such an extent that it winds up like Marquez's Macondo: wiped out by the wind and exiled from the memory of men.Stay Tuned: Next time (probably Wednesday) I will continue my discussion of this article by looking at the potential drawbacks to Kelly's plans for linking, tagging, and weaving books into the web.

Labels: book scandals, books

2 Comments:

hello Mr. Uhl.

this is not a pipe

~Rene Magritte

oui, oui:

http://www.cs.wisc.edu/~kline/not-a-pipe-magritte.jpg

nor is it an apple:

http://imagecache2.allposters.com/images/pic/AWI/f956-magritte~Ceci-n-Est-Pas-une-Pomme-Posters.jpg

Post a Comment

<< Home